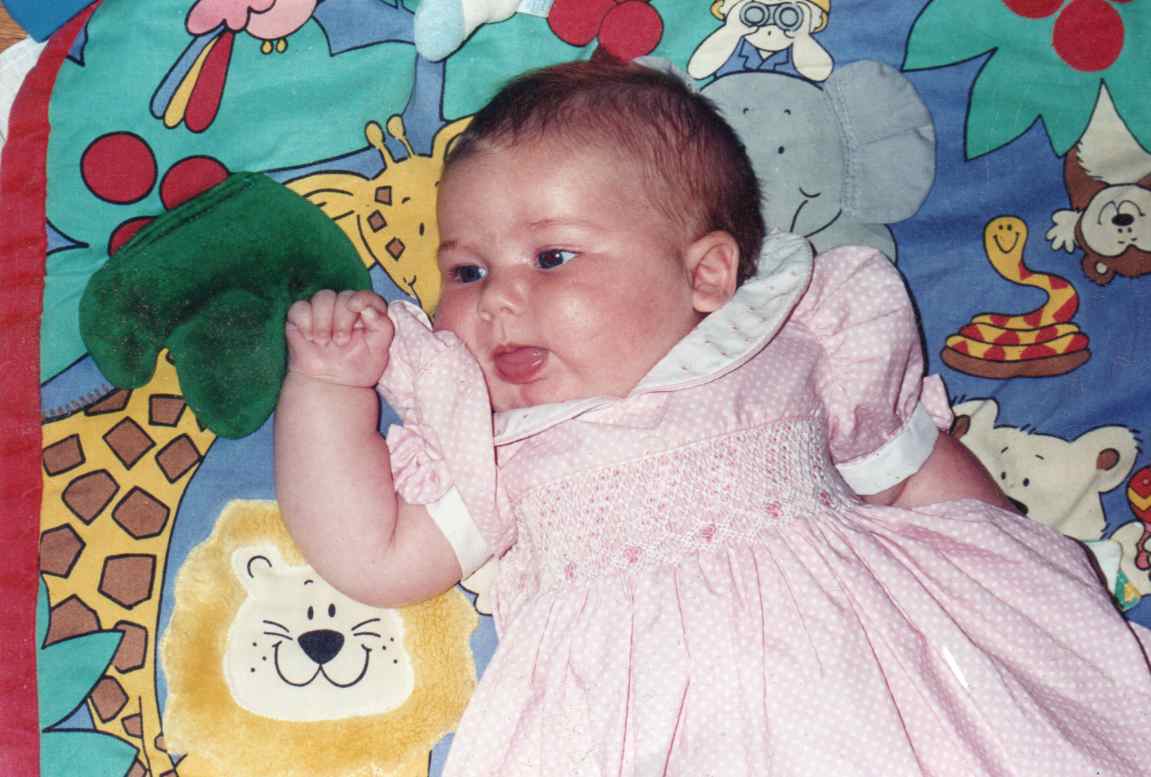

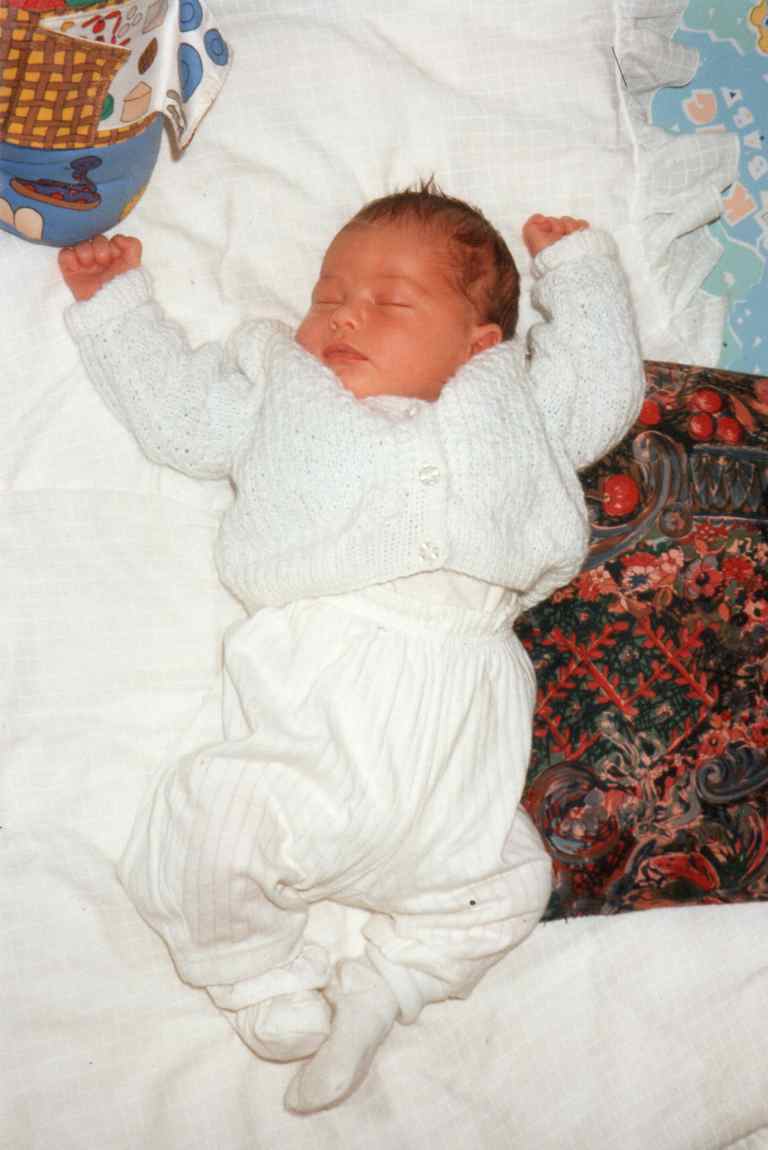

When Philippa Brownjohn welcomed her daughter, Jessica May, into the world 32 years ago, there was no sign that anything was wrong. Jessie passed all her newborn checks. She looked perfect. And for those first few weeks, Philippa and her family had no reason to imagine anything different.

“This was my second and she’s a girl..my first was a boy.” Philippa explains. “I thought maybe it’s just different. I put everything down to just being different. She was quiet, she didn’t try and lift her head or anything like that. But again, you think maybe the milestones will be slightly different for a boy to a girl.”

But at Jessie’s six‑week check, small concerns began to surface – a weak cry, difficulty lifting her head, less movement than expected. A paediatrician who had once seen a case of Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) recognised the signs. After further testing, Jessie was diagnosed with what was then called severe SMA – now known as SMA Type 1.

Philippa remembers the moment with painful clarity.

“We were basically told she would die. There was no support. No guidance. We were sent home with that diagnosis and had to get on with caring for our baby, not knowing how long we had.”

At that time, the gene hadn’t been identified, so there was no treatment. It was only after Jessie that the gene was discovered. “When I became pregnant with my next child, Harry, doctors were able to test using tissue taken from my umbilical cord and compare it with Jessie’s blood. In the space of just two years, we had moved from Jessica’s diagnosis, to losing Jessie, to becoming pregnant again – and medical understanding had moved forward with us.”

Jessie died peacefully in her father’s arms at just four and a half months old.

Her short life, and the lack of support available to her family, became the catalyst for something extraordinary: the founding of Jessie May, a charity created so that no family would ever have to face what they did, alone.

Philippa and her husband Chris received some support in High Wycombe from a hospital-at-home team. However, when they travelled to Bristol and Jessie was admitted to hospital there, they realised that no equivalent home support was available – something they had come to understand was essential for their family.

Even with medical advances, families still need emotional, practical, and specialist support – the kind Jessie May was created to provide.

“You need someone who isn’t scared. Someone who treats your child like a child, not a diagnosis. Someone you trust enough to leave your baby with, even for half an hour. That support changes everything.”

Life With SMA in the Early 1990s:

In the early 90s, SMA was rarely talked about. There was no newborn screening. No treatment. No roadmap for families.

Philippa describes a world where parents were left to navigate everything themselves:

- No specialist support after diagnosis

- No emotional guidance

- No one confident enough to care for a terminally ill baby

- No services to help families create memories at home

Even friends and relatives struggled to know how to act.

“People were horrified, but they didn’t know what to say. They didn’t know how to be with Jessie. So they kept away. You feel incredibly isolated.”

Despite everything, Philippa was determined that Jessie would experience as much of life as she possibly could. “It was important to me that she could taste things, so I’d purée food and let her try a little. I’d take her to the farm to see the animals, dress her in beautiful dresses… I just wanted her to feel like a normal little girl for the time she had left. In her short life, I managed to cram in an awful lot.”

She describes it as “going into mum mode” – doing everything she could to protect her daughter, even while knowing she couldn’t shield her from the condition itself.

Why early diagnosis is critical…

Today, the landscape for SMA looks very different.

There are treatments. There is hope. And in countries where SMA is included in newborn screening, babies can be diagnosed within 9–23 days of birth, often before symptoms appear. Early treatment can dramatically change outcomes.

But in most of the UK, including England and Wales, SMA is still not part of routine newborn screening.

That means families often don’t receive a diagnosis until symptoms develop – sometimes too late for treatment to have its full effect.

For Philippa, watching the recent news about SMA has stirred complex emotions.

“There’s a fleeting feeling of… if this had been available, Jessie might have lived longer. But mostly, it’s thank goodness. Thank goodness families now have hope.”

She is clear about one thing: early diagnosis is essential.

“If you’re offered even the tiniest bit of hope, you grab it. Early diagnosis gives families that chance.”

Advice from Philippa

When asked what she would say to parents receiving an SMA diagnosis today, Philippa paused, then spoke with the quiet certainty of someone who has walked through the darkest part of the journey.

“Go with your gut. You know your baby better than anyone. You are still their mum or dad – that doesn’t get taken away. And seek support. It’s there now, and you deserve it.”

She also shared a message for Jesy Nelson, the mother whose story recently made national headlines, and for every parent who feels overwhelmed:

“You may feel like a nurse, but you are still a mum. You are doing everything you can. And nobody can ever take that away from you.”

As newborn screening continues to be debated across the UK, Philippa’s story is a powerful reminder of what early diagnosis can change – and what support can make possible.

“I wanted to channel my grief into something positive. If I can help even one family feel less alone, then Jessie’s life has meaning far beyond her time here.”

Early diagnosis saves lives.

Support transforms them.

And hope, as Philippa shows, can carry a family through even the hardest moments.